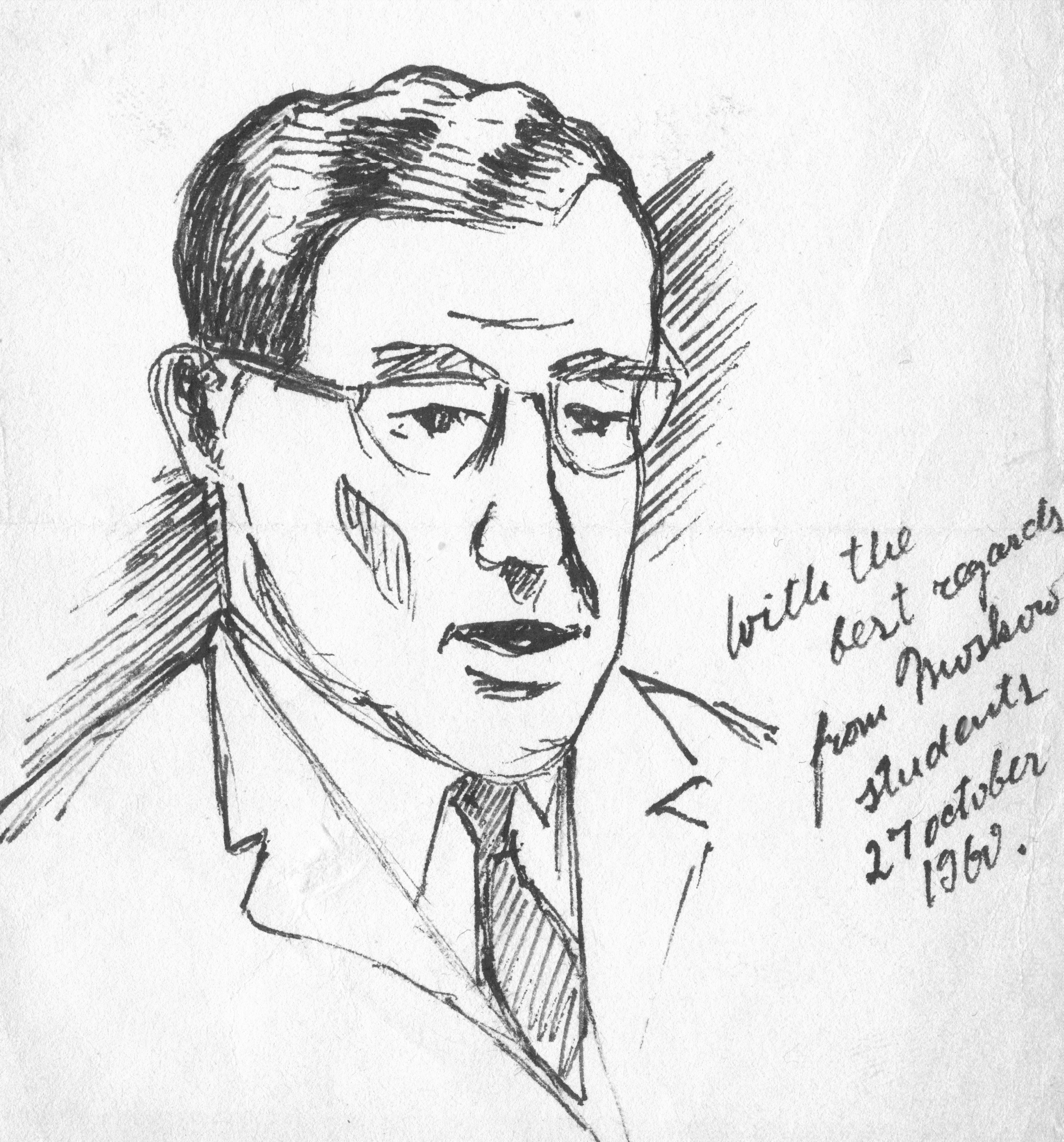

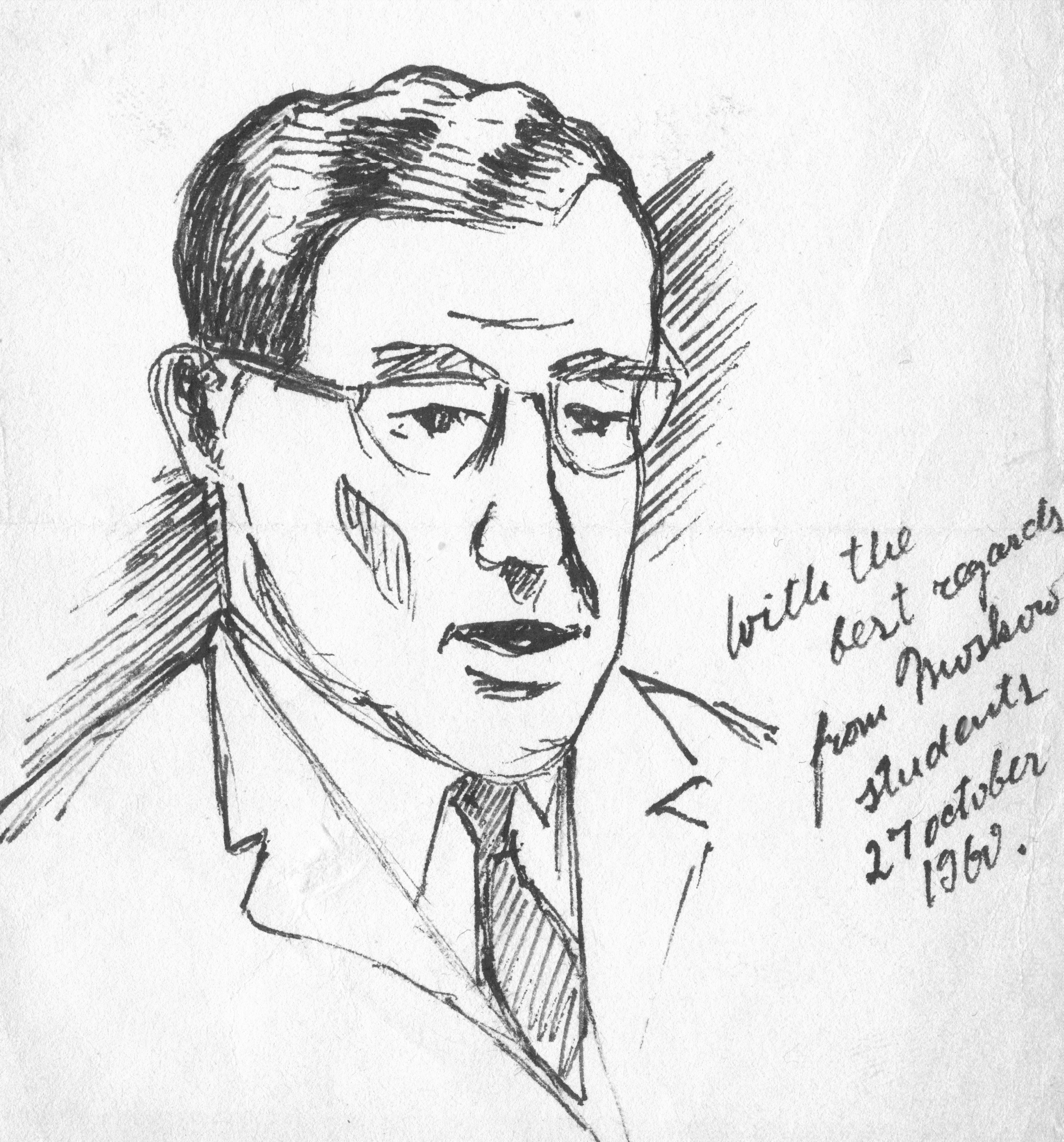

Norris Houghton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Norris Houghton (26 December 1909 – 9 October 2001) was an American stage manager, scenic designer, producer, director, theatre manager, academic, author, and public policy advocate. Houghton is known as an American expert in 20th-century Russian Theatre; as a major force in creating the "off-Broadway" movement; as a student and educator of global theater; and as an influential advocate of arts education.

Houghton taught at

Charles Norris Houghton (26 December 1909 – 9 October 2001) was an American stage manager, scenic designer, producer, director, theatre manager, academic, author, and public policy advocate. Houghton is known as an American expert in 20th-century Russian Theatre; as a major force in creating the "off-Broadway" movement; as a student and educator of global theater; and as an influential advocate of arts education.

Houghton taught at

Charles Norris Houghton (26 December 1909 – 9 October 2001) was an American stage manager, scenic designer, producer, director, theatre manager, academic, author, and public policy advocate. Houghton is known as an American expert in 20th-century Russian Theatre; as a major force in creating the "off-Broadway" movement; as a student and educator of global theater; and as an influential advocate of arts education.

Houghton taught at

Charles Norris Houghton (26 December 1909 – 9 October 2001) was an American stage manager, scenic designer, producer, director, theatre manager, academic, author, and public policy advocate. Houghton is known as an American expert in 20th-century Russian Theatre; as a major force in creating the "off-Broadway" movement; as a student and educator of global theater; and as an influential advocate of arts education.

Houghton taught at Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the nin ...

, Columbia

Columbia may refer to:

* Columbia (personification), the historical female national personification of the United States, and a poetic name for America

Places North America Natural features

* Columbia Plateau, a geologic and geographic region i ...

, and Vassar; his academic career continued at the State University of New York

The State University of New York (SUNY, , ) is a system of public colleges and universities in the State of New York. It is one of the largest comprehensive system of universities, colleges, and community colleges in the United States. Led by ...

, where he helped create the SUNY Purchase campus and served as founding Dean of Theatre and Film. He wrote many books and articles. His books and papers are preserved for study in several university and college libraries and archives.http://findingaids.princeton.edu/simpleSearch?text1=Norris+Houghton&maxdisplay=50 Abstracts and finding aids for Norris Houghton collections at Princeton libraries and listing of Princeton classes; listing for Norris Houghton as undergraduate and as alumnus. Advance from Broadway by Norris Houghton, 1941: Abstract: Consists of manuscripts for Norris Houghton's book. Advance from Broadway. Location: Manuscripts Division Call Number:C0167 Princeton Playgoers, Inc. Records, 1941–1942: Creator Princeton Playgoers, Inc. . Abstract: Princeton Playgoers, Inc. was a theater production company formed in 1942, during the wartime period when the engagements of Triangle Club were limited. Location: Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library. Princeton University Archives. Call Number:AC315 Theatre Intime Records, 1919–2011: Creator: Princeton University. Theatre Intime. Abstract: "...contains records of the Princeton University student-run theatre...and includes correspondence, clippings, photographs, playbills, Posters, scripts, designs, and promotioonal materials. Location: Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library Call Number ACO22 Miscellaneous Playscripts Collection, 1882–1961: Creator:Princeton University Library Dept. of Rare Books and Special Collections. Abstract: includes some playscripts stamped or addressed by theater agencies in Chicago, New York City, and Hollywood...others were used at McCarter Theater or by the Princeton University Players. Location: Manuscript Division Call Number TCO30 McCarter Theatre Records, 1928–2007: Creator: McCarter Theatre Center. Abstract: "The McCarter Theatre was conceived as a permanent home for the Princeton University Triangle Club. McCarter began as a booking theater but moved ...producing its own performances. The ...records document the history of the McCarter Theatre, including administration, performances and productions, and the building..." Location: Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library Princeton University Archives. Call Number: AC131 Princeton University Class Records, 1798–2011: Creator:Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library. Abstract:...consist of a diverse set of materials documenting the history and activities of Princeton University Classes during their time as undergraduates and as alumni...correspondence, newsletters, publications, photographs, and memorabilia, all of which pertain to a particular Princeton University graduating class. Location: Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library. Princeton University Archives. Call Number: AC 130Yale University Library Collections. . Archibald MacLeish Collection. Finding Aid for Phoenix Theatre: Box 19.http://www.clio.cul.columbia.edu. Finding aid Norris Houghton Book collection at Columbia University.Houghton, Norris. Entrances and Exits, Limelight Editions, 1990. 377 pages. An autobiographical memoir of Norris Houghton's lifeVassar College records. Norris Houghton curriculum vitae. The standard curriculum vitae record for faculty. Similar record at other colleges where Norris Houghton held faculty and administrative status.

Early life and introduction to the theatre

Charles Norris Houghton was born inIndianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

, Indiana, the youngest of three children of Grace Norris and Charles Houghton of Oxford, Ohio

Oxford is a city in Butler County, Ohio, United States. The population was 23,035 at the 2020 census. A college town, Oxford was founded as a home for Miami University and lies in the southwestern portion of the state approximately northwest ...

. After his parents separated in 1921 he was raised by his devoted, quiet, intellectual mother and her sister, Sarah. He remained close to them throughout their lives and their many influences included a lifetime of resilient Christian faith.

Houghton discovered the stage at age seven, when he was taken by his maternal grandfather to see E.H. Sothern and Julia Marlowe

Julia Marlowe (born Sarah Frances Frost; August 17, 1865 – November 12, 1950) was an English-born American actress, known for her interpretations of William Shakespeare's plays.

Life and career

Marlowe was born as Sarah Frances Frost at Cal ...

in ''The Taming of the Shrew

''The Taming of the Shrew'' is a comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1590 and 1592. The play begins with a framing device, often referred to as the induction, in which a mischievous nobleman tricks a drunk ...

'', and the following year to a musical brought from London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, Chu Chin Chow. Live theater ("the road") was a predominant form of entertainment, but this introduction was more than a shared cultural experience: in theater he discovered his life's plan. By age 14, Houghton offered festivals of short plays in the family home, recruiting and training the Stringscraft Players of nine young marionetteers. This period revealed the role he would pursue throughout his long life: "finding (or writing) the play, peopling it with performers, both the marionettes themselves and the manipulators of their strings; the former must be costumed, the stage decorated and lighted...and the whole put together by an impresario (myself)." By age 16 at the New Gothic style sanctuary of Tabernacle Presbyterian Church he created two Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A feast central to the Christian liturgical year ...

pageant tableaux extravaganzas for 150 performers, including coaching the choir and an organist in unfamiliar excerpts of Monteverdi and Pergolesi Pergolesi is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, (1710–1736), Italian composer, violinist, and organist

*Michael Angelo Pergolesi

Michael Angelo Pergolesi () was an Italian decorative artist from th ...

.

With a record that included captain of the debate team and senior class president, Houghton was admitted to Princeton, chosen over Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

because of Princeton's Triangle Club

The Princeton Triangle Club is a theater troupe at Princeton University. Founded in 1891, it is one of the oldest collegiate theater troupes in the United States. Triangle

premieres an original student-written musical every year, and then takes ...

, the oldest collegiate musical-comedy group in the nation. That choice gave him an early introduction to New York City theatre, an easy commute from Princeton. Many Triangle Club members became lifelong friends who helped shape modern theatre. He flourished as stage and costume designer as well as the Triangle's vice-president in this company that included Joshua Logan

Joshua Lockwood Logan III (October 5, 1908 – July 12, 1988) was an American director, writer, and actor. He shared a Pulitzer Prize for co-writing the musical ''South Pacific'' and was involved in writing other musicals.

Early years

Logan w ...

, Jose Ferrer, James Stewart

James Maitland Stewart (May 20, 1908 – July 2, 1997) was an American actor and military pilot. Known for his distinctive drawl and everyman screen persona, Stewart's film career spanned 80 films from 1935 to 1991. With the strong morality ...

, Erik Barnouw

Erik Barnouw (June 23, 1908 – July 19, 2001) was a U.S. historian of radio and television broadcasting. At the time of his death, Barnouw was widely considered to be America's most distinguished historian of broadcasting.

Life

According to ...

, Myron McCormick

Myron McCormick (February 8, 1908 – July 30, 1962) was an American actor of stage, radio and film.

Early life and education

Born in Albany, Indiana, in 1908, Walter Myron McCormick was the middle child of Walter P. and Bessie M. McCormick ...

, Alfred Dalrymple, Bretaigne Windust, and Lemuel Ayers. As an undergraduate he balanced the student-run dramatic arts organization with studies in humanistic educational traditions, including highest honors thesis research in 17th Century English Masque

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio (a public version of the masque was the pageant). A masq ...

productions.

The University Players Guild

At graduation from Princeton in 1931, Houghton had two choices: a fellowship at Princeton Graduate College to pursue English Literature or an invitation to join the University Players Guild.In the summer of 1931 "Guild" was dropped from the name of the University Players at the request of The Theatre Guild in New York City, which was then subsidizing the fledgling Group Theatre. After its 1931 summer season in West Falmouth, the University Players rebranded itself the "University Repertory Company" for its 18-week winter season in Baltimore. In the summer of 1932, it incorporated as "The Theatre Unit, Inc." See generally, Houghton, Norris, ''But Not Forgotten: The Adventure of the University Players''. William Sloan Publishers, New York: 1951. The U.P.G.—started as summer theatre inCape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mont ...

, aspiring to become a year-round venture—was founded in 1928 by Bretaigne Windust and Charles Leatherbee with involvement of Josh Logan. Houghton chose the U.P.G., which melded his interests in theatrical productions with gifted artists. As with associations during his undergraduate years, he would know his U.P.G. friends as colleagues and notables who would dominate stage and screen for decades. In Houghton's first year with the U.P.G. (the group's fourth summer season) Leatherbee, Logan and Windust espoused "the idea of theatre artists working together over a long period of time subordinating themselves to the whole and finding therein a satisfaction beyond that accruing from individual glory." Performances emerged without long rehearsals; actors learned roles in several days; sets were designed with the sketchiest of preliminary layouts. Each summer provided adventures and emotional upheavals, chronicled in Houghton's account of the U.P.G. Players, But Not Forgotten. This concept of a collective ensemble would persist throughout Houghton's career. More than a concern for long term stability, it reflected his concept of advancing beyond tradition to open channels for new forms of creativity. While the U.P.G. did not succeed as a long term venture, Houghton recalled "we had the memory of a dream that was not yet really proved vain. It had been a glorious prelude to a life in the theatre."Houghton, Norris. 1952. But Not Forgotten. Praeger. Reprinted 1975, 346 pages. Memoir of the University Players.The Oxford Companion to American Theatre 3rd edition. 2004. Oxford University Press. ed. Gerald Bordman and Thomas S. Hischak. History of Princeton University Players: "...a group founded by Bretaigne Windust and Charles Leatherbee in 1928 as the University Players Guild. ...In the last year the company changed its name to the Theatre Unit, Inc., ... Among figures... who ... became famous were Henry Fonda

Henry Jaynes Fonda (May 16, 1905 – August 12, 1982) was an American actor. He had a career that spanned five decades on Broadway and in Hollywood. He cultivated an everyman screen image in several films considered to be classics.

Born and ra ...

, Joshua Logan, Myron McCormick, Mildred Natwick, Kent Smith, James Stewart, and Margaret Sullavan

Margaret Brooke Sullavan (May 16, 1909 – January 1, 1960) was an American stage and film actress.

Sullavan began her career onstage in 1929 with the University Players. In 1933, she caught the attention of film director John M. Stahl and had ...

. Norris Houghton ... wrote the history of the company in ''But Not Forgotten''."

Throughout this period, ranging from full to empty houses, Houghton never regretted rejecting the offer of assistant stage manager job for ''Mourning Becomes Electra

''Mourning Becomes Electra'' is a play cycle written by American playwright Eugene O'Neill. The play premiered on Broadway at the Guild Theatre on 26 October 1931 where it ran for 150 performances before closing in March 1932, starring Lee Baker ...

'' with New York City's Theatre Guild

The Theatre Guild is a theatrical society founded in New York City in 1918 by Lawrence Langner, Philip Moeller, Helen Westley and Theresa Helburn. Langner's wife, Armina Marshall, then served as a co-director. It evolved out of the work of th ...

, the nation's ace theatrical production company. Such coveted opportunities reflected both on Houghton's rapidly growing reputation and the evolution of his unique life plan; similar conflicts in decision making would recur throughout his life. History shows that he was guided by Leatherbee's advice to avoid alliance with the dated, no matter how distinguished. Houghton would persist in becoming a contributor to the future rather than remaining in the safety of the past.

New York to Moscow

Houghton was both an advocate of global theater and dedicated to the live theater of New York City. He moved there to await his chance, livened by his Princeton companions and the U.P.G. weekly beer parties on West 47th Street that brought together the older "alumni" and new young aspirants such as Burgess Meredith,Broderick Crawford

William Broderick Crawford (December 9, 1911 – April 26, 1986) was an American stage, film, radio, and television actor, often cast in tough-guy roles and best known for his Oscar- and Golden Globe-winning portrayal of Willie Stark in ''All th ...

, John Beal and Karl Malden

Karl Malden (born Mladen George Sekulovich; March 22, 1912 – July 1, 2009) was an American actor. He was primarily a character actor, who according to Robert Berkvist, "for more than 60 years brought an intelligent intensity and a homespun aut ...

. His first break came with an appointment as assistant to Robert Edmond Jones, an acclaimed designer who moved stage design into an integral part of stage productions; scenic design and artistic direction was a lifelong passion of Houghton's. Varied opportunities followed but none included a permanent position, so Houghton accepted a Guggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowships are grants that have been awarded annually since by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to those "who have demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the art ...

for a year of study abroad. Following the suggestion of Henry Allen Moe, Guggenheim Director General, the fellowship

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher educatio ...

transformed Houghton's career: it introduced him to the renowned but little understood Russian theatre, and led to a future that included expository writing appealing to both academic experts and a public audience. The experience and his writings led to his reputation as the preeminent American student and teacher of the Russian theater, illumined by his relationship with the major 20th-century Russian theater figure, Stanislavski

Konstantin Sergeyevich Stanislavski ( Alekseyev; russian: Константин Сергеевич Станиславский, p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin sʲɪrˈgʲejɪvʲɪtɕ stənʲɪˈslafskʲɪj; 7 August 1938) was a seminal Soviet Russian t ...

. This year of study also ripened to a global perspective that remained a constant throughout his life.Houghton, Norris. 1936. Moscow Rehearsals. Octagon Books. Reprinted 1962, 1975, 291 pages.New York Times. April 1936. Review by Lewis Nichols of Moscow Rehearsals: "The Stage Behind the Soviet Proscenium; Moscow Rehearsals."Houghton, Norris. 1962. Return Engagement, Holt, Rinehart, Winston, 214 pages Memoir of repeated visit to Russian theater.New York Times. April 1962. Review by Howard Taubman of The Theatre in the USSR by Norris Houghton

Moscow rehearsals: the definitive work on Russian theatre

Gaining admission at audience level to the famed Russian theatre, Houghton experienced art as a revered and honored cultural mission in contrast to the glitter of New York theatre. Welcomed by giants of Russian theatre: Konstantin Stanislavski, distinguished actress Olga Leonardovna Knipper-Chekhova (Anton Chekhov

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (; 29 January 1860 Old Style date 17 January. – 15 July 1904 Old Style date 2 July.) was a Russian playwright and short-story writer who is considered to be one of the greatest writers of all time. His career ...

's widow), Alexander Tairov, and the revolutionary director Vsevolod Meierhold, Houghton was accepted at rehearsals at Stanislavski's world-famous Moscow Art Theatre

The Moscow Art Theatre (or MAT; russian: Московский Художественный академический театр (МХАТ), ''Moskovskiy Hudojestvenny Akademicheskiy Teatr'' (МHАТ)) was a theatre company in Moscow. It was f ...

—an essential for any informed scholarship about Russian theatre. Houghton noted that observing Stanislavski gave him "an understanding of the difference between Soviet and American attitude toward the arts"—a distinction not complimentary to the American perspective. Houghton's career coincided with the emergence of the postmodern era in the arts, and he was a keen observer of its effect in the theater and a reporter whose writing clarified complex concepts for his readers. Observing Russia's Realistic Theater, with its goal of comingling audience and actor, Houghton noted "...spectators and actors look much the same... there will be Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

uniforms on the stage and in the house; there will be shawl-shrouded women and rough-bloused men in both places." These experiences enabled Norris Houghton to become the preeminent American authority on Russian theatre and challenged him to look beyond fashionable modes, to understand art through experiential training, and to infuse those values in his productions. Konstantin Stanislavsky presented his book, My Life In Art, to Houghton with the inscription: "To Charles Norris Houghton, my dear comrade in art, with this friendly advice: love the art in yourself and not yourself in art."

In 1935, the first draft of Moscow Rehearsals complete, Houghton returned to New York City. Stage manager of a production of Libel! directed by Otto Preminger

Otto Ludwig Preminger ( , ; 5 December 1905 – 23 April 1986) was an Austrian-American theatre and film director, film producer, and actor.

He directed more than 35 feature films in a five-decade career after leaving the theatre. He first gai ...

in his first American appearance, the play was still running when reviews of Houghton's book on the Russian theatre hit the presses. They were so extraordinary that Houghton said "I was taken aback." Renowned critic John Mason Brown

John Mason Brown (July 3, 1900 – March 16, 1969) was an American drama critic and author.Van Gelder, Lawrence (March 17, 1969). "John Mason Brown, Critic, Dead." ''The New York Times''

Life

Born in Louisville, Kentucky, he graduated from Harva ...

,writing in ''The New York Times,'' said that Mr. Houghton's book "ought to be devoured by every director, manager, actor and critic in our theater."http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2175023. Great Russian_Short_Stories Review of Norris Houghton edited book. The book's success increased led to requests that Houghton travel and report on regional, national, and international theater. He gained better understanding of the diversity of theater outside of New York.http://www.betterworldbooks.com/advance-from-broadway-id-0836956532.aspx Lists Norris Houghton books and reviews.http://www.optimumgambling.com/section/Books/Books/%27Norris%20Houghton%27 Lists Norris Houghton books.Houghton, Norris, ed. 1958. Great Russian Short Stories, Dell Laurel Editions, 383 pages Selection of Russian Short Stories and their literary significance.

Challenges and legacies from Broadway and beyond

In those pre-WWII years, Houghton was engaged as stage manager on various productions, working with former U.P.G. friends,Kent Smith

Frank Kent Smith (March 19, 1907 – April 23, 1985) was an American actor who had a lengthy career in film, theatre and television.

Early years

Smith was the son of Mr. and Mrs. James E. Smith. He was born in New York City and was educated ...

, Jose Ferrer, Myron McCormick, and some established stars such as Ethel Barrymore

Ethel Barrymore (born Ethel Mae Blythe; August 15, 1879 – June 18, 1959) was an American actress and a member of the Barrymore family of actors. Barrymore was a stage, screen and radio actress whose career spanned six decades, and was regarde ...

, Ruth Gordon

Ruth Gordon Jones (October 30, 1896 – August 28, 1985) was an American actress, screenwriter, and playwright. She began her career performing on Broadway at age 19. Known for her nasal voice and distinctive personality, Gordon gained internati ...

, Claude Rains

William Claude Rains (10 November 188930 May 1967) was a British actor whose career spanned almost seven decades. After his American film debut as Dr. Jack Griffin in ''The Invisible Man'' (1933), he appeared in such highly regarded films as '' ...

. In 1939 he became art director of the St. Louis Municipal Opera

The St. Louis Municipal Opera Theatre (commonly known as The Muny) is an amphitheater located in St. Louis, Missouri. The theatre seats 11,000 people with about 1,500 free seats in the last nine rows that are available on a first come, first se ...

. The "Muny," as its devoted audience call it, then held summer performances on an enormous stage in Forest Park before 11,000 people seated on an open hillside. Houghton's success in meeting the challenge of designing scenes for an outdoor stage that included two gigantic oak trees led to three seasons of invitations as art director.http://www.muny.org History of the St. Louis Municipal Opera; for three years Norris Houghton was art directorPittsburgh Post Gazette. May 1940. Local Scrappings. Reports on visit of Norris Houghton, Artistic Director of St. Louis Municipal Opera, to gather material for Rockefeller Foundation Grant on theater in America.Tulane Drama Review. 1959. MIT Press Journals publisher. Article: The Phoenix Has Two Heads by Albert Bermel. Summarizes transition of Phoenix from Theater Inc; describes Phoenix' deficits as exemplary of high costs of theater; notes Norris Houghton's experiences prior to the Phoenix, including Art Director of the St. Louis Municipal Opera.

In 1940, he was approached by Harcourt Brace

Harcourt () was an American publishing firm with a long history of publishing fiction and nonfiction for adults and children. The company was last based in San Diego, California, with editorial/sales/marketing/rights offices in New York City an ...

to write a book on American theatre beyond Broadway. Funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, Houghton criss-crossed the U.S.A., visiting 70 stages. Children's theatre, college campus theatre, outdoor history pageants, union workers' theatre, summer stock, middle-American "nightclub" variety theatres, the "road" sites for touring Broadway hits, community theatres often more social than artistic: this montage was critiqued, applauded, reprimanded, and encouraged as evidence of theatrical aspirations more democratic than the commercial Broadway model. Enthused by these experiences, they heightened Houghton's disappointment about the dearth of original plays by young Americans, and the failure of recognized American playwrights to ally themselves with regional theatres. In the resulting book, Advance From Broadway, Houghton asserted "...my declaration of independence from the commercial theatre and a call for decentralization of our professional stage." Houghton resonated to the parting advice of a "living legend" among theatre aficionados, Edward Sheldon

Edward Brewster Sheldon (Chicago, Illinois, February 4, 1886 – April 1, 1946, New York City) was an American dramatist. His plays include ''Salvation Nell'' (1908) and ''Romance'' (1913), which was made into a motion picture with Greta Garbo.

...

, who had advised him: "Seek out the people who put these things in motion. They're what matter." Many fine men and women were out there in America. "It's they I must remember."Houghton, Norris. 1941. Advance from Broadway, Harcourt Brace & Company; reprinted 1971, 416 pages. Description of Norris Houghton's country-wide tour of regional theaters.The Cambridge Guide to American Theatre. 2007 Cambridge University Press. Covers American theatre from its earliest history to the present, with special attention given to contemporary theatre throughout the United States.

Houghton's call for theatrical renaissance and independence from Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

strictures was overwhelmed temporarily by World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The war became a memorable interlude in Houghton's life, after recruitment into a service that would utilize his skills in the Russian language. In early 1945 he became part of the support staff for the Big Three conference

A conference is a meeting of two or more experts to discuss and exchange opinions or new information about a particular topic.

Conferences can be used as a form of group decision-making, although discussion, not always decisions, are the main p ...

in Yalta

Yalta (: Я́лта) is a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Crimea ...

, a meeting that shaped post-war Europe. He later chronicled his experiences in The New Yorker as "That Was Yalta: Worm's Eye View." His war experiences led into encounters that reflected the charisma of this man, including a meeting with Michael Redgrave in a piano bar in London where Lt. Houghton (j.g.) USNR had been posted as part of a naval communications unit. That encounter blossomed into a lifelong friendship with the Redgraves and a production of Macbeth starring Michael, directed by Houghton, in London and New York in 1947 and 1948.The Entertainment Review. May 1948. Vol 79 Issue 4 p 93. Review of "Macbeth" by Lewis Theophilus. Abstract: The article reviews the theatrical production "Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

," directed by Norris Houghton and performed by Michael Redgrave

Sir Michael Scudamore Redgrave CBE (20 March 1908 – 21 March 1985) was an English stage and film actor, director, manager and author. He received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in ''Mourning Becomes Elect ...

and Flora Robson

Dame Flora McKenzie Robson (28 March 19027 July 1984) was an English actress and star of the theatrical stage and cinema, particularly renowned for her performances in plays demanding dramatic and emotional intensity. Her range extended from q ...

at the National Theater in New York. Accession #35237200

The decade following World War II marked a period of change in American theatre. He enjoyed a key role in this period, including the associate editorship of a primary resource in the theatrical world, ''Theatre Arts''. In 1945 he became director, producer, and pioneer of what would become known as Off-Broadway

An off-Broadway theatre is any professional theatre venue in New York City with a seating capacity between 100 and 499, inclusive. These theatres are smaller than Broadway theatres, but larger than off-off-Broadway theatres, which seat fewer tha ...

. In two triumphal seasons, the ''Theatre Inc'' group he helped found presented Gertrude Lawrence

Gertrude Lawrence (4 July 1898 – 6 September 1952) was an English actress, singer, dancer and musical comedy performer known for her stage appearances in the West End of London and on Broadway in New York.

Early life

Lawrence was born Gertr ...

in ''Pygmalion

Pygmalion or Pigmalion may refer to:

Mythology

* Pygmalion (mythology), a sculptor who fell in love with his statue

Stage

* ''Pigmalion'' (opera), a 1745 opera by Jean-Philippe Rameau

* ''Pygmalion'' (Rousseau), a 1762 melodrama by Jean-Jacques ...

'', London's Old Vic

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

*Old, Baranya, Hungary

* Old, Northamptonshire, England

*Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, Ma ...

in repertory of four classics featuring, among others, Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the Theatre of the U ...

, Ralph Richardson

Sir Ralph David Richardson (19 December 1902 – 10 October 1983) was an English actor who, with John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier, was one of the trinity of male actors who dominated the British stage for much of the 20th century. He wo ...

, and Margaret Leighton

Margaret Leighton, CBE (26 February 1922 – 13 January 1976) was an English actress, active on stage and television, and in film. Her film appearances included (her first credited debut feature) in Anatole de Grunwald's ''The Winslow Boy'' (1 ...

; ''The Playboy of the Western World

''The Playboy of the Western World'' is a three-act play written by Irish playwright John Millington Synge and first performed at the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, on 26 January 1907. It is set in Michael James Flaherty's public house in County Mayo (o ...

'' with Burgess Meredith, and the "primitive and violent" ''Macbeth'' on which Redgrave and Houghton had collaborated originally in London. Brooks Atkinson

Justin Brooks Atkinson (November 28, 1894 – January 14, 1984) was an American theatre critic. He worked for ''The New York Times'' from 1922 to 1960. In his obituary, the ''Times'' called him "the theater's most influential reviewer of his ...

reviewed ''Macbeth'': "Under Norris Houghton's direction, ''Macbeth'' gives us, for the first time in my memory, the sweep and excitement of the drama as a whole." He called it "a unified work of the theatre."

A major motivation: the rejection of Billy Budd

These experiences crystallized into action by a series of events following Houghton's receipt of a manuscript dramatizingHerman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American people, American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his bes ...

's '' Billy Budd, Foretopman'' co-authored by his fellow Princeton alumnus Robert Chapman. Successfully finding backing for a production of Louis O. Coxe and Chapman's ''Billy Budd

''Billy Budd, Sailor (An Inside Narrative)'' is a novella by American writer Herman Melville, left unfinished at his death in 1891. Acclaimed by critics as a masterpiece when a hastily transcribed version was finally published in 1924, it quick ...

'', with restaging by Josh Logan, the show opened on Broadway on February 10, 1951. Despite laudatory reviews by Brooks Atkinson and the attempt of others to prolong the run, the play closed after three months. Houghton learned that the Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

panel had selected this drama for its annual award, but nothing came of it. This frustrating episode led Houghton to look for theater not subject to Broadway's hit/flop syndrome.Chronicle of the Pulitzer Prizes for Drama: Discussions, Decisions and Documents. 2009. Heinz-Dietrich Fischer, Erika J. Fischer. 2009. Walter de Gruyter 432 pages. Documents the complete history ... of ...awards in the category drama... mainly based on primary sources from the Pulitzer Prize Office... The most important sources are the confidential jury protocols, reproduced ... as facsimiles for the first time... providing detailed information about each year's evaluation process. Includes letter of the rejected recommendation for Pulitzer Prize to Billy Budd.

Television was not a viable alternative. In his brief engagement as producer/director of the CBS Television Workshop

''CBS Television Workshop'' is an American anthology series that aired on CBS from January to April 1952. The series is noted for featuring early television appearances of several well known actors, including Audrey Hepburn, James Dean, Sidne ...

, Houghton directed 14 programs. The series ended when CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainmen ...

failed to find a show sponsor and Houghton found the TV environment "decivilizing," not allowing time for any of the cultural activities that enriched the life he might bring to his productions.https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0534274/fullcredits#cast. Productions of CBS TV Workshop during Norris Houghton's directorship.

The phoenix rises

Houghton's commitment to an off-Broadway theater coincided with a confluence of experimental theatres in the 1950s, including theLiving Theatre

The Living Theatre is an American theatre company founded in 1947 and based in New York City. It is the oldest experimental theatre group in the United States. For most of its history it was led by its founders, actress Judith Malina and painter/po ...

of Julian Beck

Julian Beck (May 31, 1925 – September 14, 1985) was an American actor, stage director, poet, and painter. He is best known for co-founding and directing The Living Theatre, as well as his role as Reverend Henry Kane, the malevolent preacher i ...

and Judith Malina

Judith Malina (June 4, 1926 – April 10, 2015) was a German-born American actress, director and writer. With her husband, Julian Beck, Malina co-founded The Living Theatre, a radical political theatre troupe that rose to prominence in New York C ...

, focused on poetic dramas and the Circle in the Square

The Circle in the Square Theatre is a Broadway theater at 235 West 50th Street, in the basement of Paramount Plaza, in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. It is one of two Broadway theaters that use a thrust stage that extends ...

organized by Jose Quintero and Theodore Mann

Theodore Mann, birth name Goldman, (May 13, 1924 – February 24, 2012) was an American theatre producer and director and the Artistic Director of the Circle in the Square Theatre School.

Mann co-founded Circle in the Square Theatre, widely r ...

that showcased young talent in revivals of plays not commercially successful on Broadway. In 1953 Houghton and an acquaintance, T. Edward Hambleton, agreed to establish a new theater based on a mutual "off-Broadway" dream. They agreed on principles that emerged from Houghton's two decades of experiences: their theatre would be separate from Times Square

Times Square is a major commercial intersection, tourist destination, entertainment hub, and neighborhood in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. It is formed by the junction of Broadway, Seventh Avenue, and 42nd Street. Together with adjacent ...

; it would be a "permanent" company; they would produce four to five plays for limited engagements; in contrast to the star system, actors would be listed alphabetically; the ticket price would be half of Broadway's top, with tickets available also for one dollar; the management structure would be a traditional limited partnership, but contributors would be asked to fund an entire season rather than each production. They named it the Phoenix

Phoenix most often refers to:

* Phoenix (mythology), a legendary bird from ancient Greek folklore

* Phoenix, Arizona, a city in the United States

Phoenix may also refer to:

Mythology

Greek mythological figures

* Phoenix (son of Amyntor), a ...

, and it operated from 1953 to 1982, managed in its later years by Hambleton as Houghton moved into academia. The Phoenix experiment became a pioneer in the off-Broadway movement; its origins and history are perhaps the accomplishments for which Houghton is best known.http://www.ibdb.com/person.php?id=24496. Internet Broadway Database archive. Lists Norris Houghton productions from 1937 to 1982; lists Theatre Incorporated productions, T. Edward Hambleton and Norris Houghton, Managing Directors, 1958-1961https://query.nytimes.com/search/sitesearch/#/Phoenix+Theater New York Times listing of openings and reviews of Phoenix Productionshttp://www.lortel.org/lla_archive/ Internet Off-Broadway Database. Lists Phoenix plays 1953–1965Hambleton, T. Edward and Houghton, Norris. 1954. Theatre Arts Magazine. Article "Phoenix on the Wing."Educational Theatre Journal Coverage: 1949-1978 (Vols. 1–30) Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Descriptions of the off-Broadway movement including the Phoenix.

They compromised on a deserted movie house on East 12th Street. Located far from Broadway, larger than they wanted, its design was adequate, if not ideal, for their productions. The Phoenix opened December 1, 1953: the first production was Madam Will You Walk?, the posthumous performance of a new play by deceased Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

winner Sidney Howard

Sidney Coe Howard (June 26, 1891 – August 23, 1939) was an American playwright, dramatist and screenwriter. He received the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1925 and a posthumous Academy Award in 1940 for the screenplay for ''Gone with the Wind''. ...

, starring Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy. A midnight review on CBS cited "an exciting and new theatrical adventure born tonight amidst laughter and hearty applause of 1200 enthusiastic people who stirred away from their TV sets to see a very witty and provocative play by Sidney Howard. The evening was exciting in another way, however, because it saw a theatre which had been dark brought to light—brought to life again...When the lights are on at the Phoenix—and you are the only ones who can keep them on—there's theatre magic in abundance to be heard and seen and enjoyed."

Good reviews alone could not keep the lights on because opening night was the eve of a Manhattan newspaper strike. Curtain speeches appealing to audiences to spread the news in New York City yielded a sold-out Saturday night. The next production was ''Coriolanus

''Coriolanus'' ( or ) is a tragedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1605 and 1608. The play is based on the life of the legendary Roman leader Caius Marcius Coriolanus. Shakespeare worked on it during the same ye ...

'', starring Robert Ryan

Robert Bushnell Ryan (November 11, 1909 – July 11, 1973) was an American actor and activist. Known for his portrayals of hardened cops and ruthless villains, Ryan performed for over three decades. He was nominated for the Academy Award for ...

and Mildred Natwick

Mildred Natwick (June 19, 1905 – October 25, 1994) was an American actress. She won a Primetime Emmy Award and was nominated for an Academy Award and two Tony Awards.

Early life

Natwick was born in Baltimore, Maryland, the daughter of Mildre ...

, directed by John Houseman

John Houseman (born Jacques Haussmann; September 22, 1902 – October 31, 1988) was a Romanian-born British-American actor and producer of theatre, film, and television. He became known for his highly publicized collaboration with director ...

, proclaimed by Morehouse of the ''New York World-Telegram and Sun

The ''New York World-Telegram'', later known as the ''New York World-Telegram and The Sun'', was a New York City newspaper from 1931 to 1966.

History

Founded by James Gordon Bennett Sr. as ''The Evening Telegram'' in 1867, the newspaper began ...

'' as "one of the finest Shakespearean productions I've seen in a lifetime of playgoing." Then came the challenge of an off-beat musical take on the Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and has ...

, '' The Golden Apple'', written by John LaTouche, music by Jerome Moross

Jerome Moross (August 1, 1913July 25, 1983) was an American composer best known for his music for film and television. He also composed works for symphony orchestras, chamber ensembles, soloists and musical theater, as well as orchestrating score ...

. Brooks Atkinson called it "a light, gay, charming production...the only literate new musical of the season..", while others, notably Wolcott Gibbs in ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

'' quibbled "Oh I liked her, but not very much." Mixed reviews recurred throughout Phoenix' life, but the New York Drama Critics' Circle named ''The Golden Apple'' the Best New Musical of the 1953/54 season, and it received the cover and inside-spread photo coverage of ''Life Magazine'' and was transferred to Broadway by Roger L. Stevens and Alfred de Liagre.http://www.dramacritics.org/dc pastawards.html. Drama Critics Awards, 1953/1954, the year the Phoenix production won the award.

To conclude the Phoenix opening season, Houghton approached Montgomery Clift

Edward Montgomery Clift (; October 17, 1920 – July 23, 1966) was an American actor. A four-time Academy Award nominee, he was known for his portrayal of "moody, sensitive young men", according to ''The New York Times''.

He is best remembered ...

, an acquaintance since Houghton designed the set for Clift's 1939 Broadway debut in the Theatre Guild's Dame Nature. The outcome was ''The Seagull

''The Seagull'' ( rus, Ча́йка, r=Cháyka, links=no) is a play by Russian dramatist Anton Chekhov, written in 1895 and first produced in 1896. ''The Seagull'' is generally considered to be the first of his four major plays. It dramatises t ...

'' with Clift as Constantin and Houghton as director. Other major roles were taken by Maureen Stapleton

Lois Maureen Stapleton (June 21, 1925 – March 13, 2006) was an American actress. She received numerous accolades, including an Academy Award, a Golden Globe Award, a BAFTA Award, a Primetime Emmy Award, and two Tony Awards, in addition to ...

, June Walker

: ''For the American activist and former Hadassah leader, see June Walker (Hadassah)''

June Walker (June 14, 1900 – February 3, 1966) was an American stage and film actress.

Early years

Walker was born in New York City on June 14, 1900, an ...

, George Voskovec

Jiří Voskovec (), born Jiří Wachsmann and known in the United States as George Voskovec (June 19, 1905 – July 1, 1981) was a Czech actor, writer, dramatist, and director who became an American citizen in 1955. Throughout much of his career ...

, Sam Jaffe

Shalom "Sam" Jaffe (March 10, 1891 – March 24, 1984) was an American actor, teacher, musician, and engineer. In 1951, he was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance in '' The Asphalt Jungle'' (1950) and ap ...

, Will Greer, John Fiedler

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Second E ...

and Judith Evelyn

Judith Evelyn (born Evelyn Morris, March 20, 1909 – May 7, 1967) was an American-Canadian stage and film actress who appeared in around 50 films and television series.

Early years

Evelyn was born Evelyn Morris''

Norris Houghton

at

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

''. May 1954. Amusements. Review by Brooks Atkinson. "''The Sea Gull'', an incomparably beautiful play, has fallen heir to an interesting performance, which opened at the Phoenix last evening..."

The Phoenix opening season was judged a resounding success and led to many subsequent award-winning productions. These attracted the talent of British actors Pamela Brown, Michael

Michael may refer to:

People

* Michael (given name), a given name

* Michael (surname), including a list of people with the surname Michael

Given name "Michael"

* Michael (archangel), ''first'' of God's archangels in the Jewish, Christian an ...

and Rachel Redgrave

Rachel () was a Biblical figure, the favorite of Jacob's two wives, and the mother of Joseph and Benjamin, two of the twelve progenitors of the tribes of Israel. Rachel's father was Laban. Her older sister was Leah, Jacob's first wife. Her aun ...

, Peggy Ashcroft

Dame Edith Margaret Emily Ashcroft (22 December 1907 – 14 June 1991), known professionally as Peggy Ashcroft, was an English actress whose career spanned more than 60 years.

Born to a comfortable middle-class family, Ashcroft was deter ...

; directors and producers Elia Kazan

Elia Kazan (; born Elias Kazantzoglou ( el, Ηλίας Καζαντζόγλου); September 7, 1909 – September 28, 2003) was an American film and theatre director, producer, screenwriter and actor, described by ''The New York Times'' as "one o ...

, John Houseman

John Houseman (born Jacques Haussmann; September 22, 1902 – October 31, 1988) was a Romanian-born British-American actor and producer of theatre, film, and television. He became known for his highly publicized collaboration with director ...

, Robert Whitehead

Robert Whitehead (3 January 1823 – 14 November 1905) was an English engineer who was most famous for developing the first effective self-propelled naval torpedo.

Early life

He was born in Bolton, England, the son of James Whitehead, ...

, Alfred de Liagre; writers and designers Sidney Howard, Robert Sherwood, John Latouche, Jerome Moross

Jerome Moross (August 1, 1913July 25, 1983) was an American composer best known for his music for film and television. He also composed works for symphony orchestras, chamber ensembles, soloists and musical theater, as well as orchestrating score ...

, Donald Oenslager Donald Oenslager (March 7, 1902 – June 11, 1975) was an American scenic designer who won the Tony Award for Best Scenic Design.

Biography

Oenslager was born in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and attended Harvard University, graduating in 1923. He becam ...

, Bill

Bill(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Banknote, paper cash (especially in the United States)

* Bill (law), a proposed law put before a legislature

* Invoice, commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer

* Bill, a bird or animal's beak

Plac ...

and Jean Eckart

William and Jean Eckart were a husband-and-wife team of theatre designers in the 1950s and 1960s. They designed sets, costumes, and lighting for many productions, including ''Mame'', ''Here's Love'', ''Damn Yankees'', ''Once Upon a Mattress'', ''T ...

; American stars Hume Cronyn

Hume Blake Cronyn Jr. OC (July 18, 1911 – June 15, 2003) was a Canadian-American actor and writer.

Early life

Cronyn, one of five children, was born in London, Ontario, Canada. His father, Hume Blake Cronyn, Sr., was a businessman and ...

, Jessica Tandy

Jessie Alice Tandy (7 June 1909 – 11 September 1994) was a British-American actress. Tandy appeared in over 100 stage productions and had more than 60 roles in film and TV, receiving an Academy Award, four Tony Awards, a BAFTA, a Golden Glob ...

, Millie Natwick, Mildred Dunnock

Mildred Dorothy Dunnock (January 25, 1901 – July 5, 1991) was an American stage and screen actress. She was twice nominated for an Academy Award: first ''Death of a Salesman'' in 1951, then ''Baby Doll'' in 1956.

Early life

Born in Baltimore, ...

, Robert Ryan

Robert Bushnell Ryan (November 11, 1909 – July 11, 1973) was an American actor and activist. Known for his portrayals of hardened cops and ruthless villains, Ryan performed for over three decades. He was nominated for the Academy Award for ...

, Montgomery Clift, Kaye Ballard

Kaye Ballard (November 20, 1925 – January 21, 2019) was an American actress, comedian, and singer.

Early life

Ballard was born Catherine Gloria Balotta in Cleveland, Ohio, one of four children born to Italian immigrant parents, Lena (née Nac ...

; professional colleagues and friends, Howard Lindsay

Howard Lindsay, born Herman Nelke, (March 29, 1889 – February 11, 1968) was an American playwright, librettist, director, actor and theatrical producer. He is best known for his writing work as part of the collaboration of Lindsay and Crouse ...

, Russel and Anna Crouse, Jo Mielziner

Joseph "Jo" Mielziner (March 19, 1901 – March 15, 1976) was an American theatrical scenic, and lighting designer born in Paris, France. He was described as "the most successful set designer of the Golden era of Broadway", and worked on both sta ...

, Oscar Hammerstein II

Oscar Greeley Clendenning Hammerstein II (; July 12, 1895 – August 23, 1960) was an American lyricist, librettist, theatrical producer, and (usually uncredited) director in the musical theater for almost 40 years. He won eight Ton ...

, Clinton Wilder, Peggy Wood

Mary Margaret Wood (February 9, 1892 – March 18, 1978) was an American actress of stage, film, and television. She is best remembered for her performance as the title character in the CBS television series ''Mama'' (1949–1957), for which sh ...

, William Inge

William Motter Inge (; May 3, 1913 – June 10, 1973) was an American playwright and novelist, whose works typically feature solitary protagonists encumbered with strained sexual relations. In the early 1950s he had a string of memorable Broad ...

, Arthur Miller.New York Times. May 1956. Article by Lewis Funke. "Gossip of the Rialto; New Revue and Drama Off Broadway" That new face the Phoenix Theater plans to put on in the fall already appears ... have made him the critics darling, is figuring on a Broadway invasion in the fall.New York Times. Arts and Leisure. February 1957. Review by Brooks Atkinson. "On Second Avenue; Phoenix and Off-Broadway Theatres Stage Plays of Literary Content." "Both plays were entitled to expect a more cordial reception. Shakespeare... Just how the Little Broadway of Second Avenue has high standards..."New York Times. June 1965. Article by Sam Zolotow. Phoenix Director Wins $500 Prize; ...the repertory company at the Phoenix Theater is this year's winner of the Lola D'Annunzio Award for his "outstanding contribution to the Off Broadway theater... Examples of the span of productions include: '' The Doctor's Dilemma'' (George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

), ''The Master Builder

''The Master Builder'' ( no, Bygmester Solness) is a play by Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen.

It was first published in December 1892 and is regarded as one of Ibsen's more significant and revealing works.

Performance

The play was published ...

'' (Henrik Ibsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright and theatre director. As one of the founders of modernism in theatre, Ibsen is often referred to as "the father of realism" and one of the most influential playw ...

), '' Story of a Soldier'' (music drama, Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the ...

), ''Six Characters in Search of an Author

''Six Characters in Search of an Author'' ( it, Sei personaggi in cerca d'autore, link=no ) is an Italian play by Luigi Pirandello, written and first performed in 1921. An absurdist fiction, absurdist metatheatrical, metatheatric play about th ...

'' (Luigi Pirandello

Luigi Pirandello (; 28 June 1867 – 10 December 1936) was an Italian dramatist, novelist, poet, and short story writer whose greatest contributions were his plays. He was awarded the 1934 Nobel Prize in Literature for "his almost magical power ...

), ''The Mother of Us All

''The Mother of Us All'' is a two-act opera composed by Virgil Thomson to a libretto by Gertrude Stein. Thomson and Stein met in 1945 to begin the writing process, almost twenty years after their first collaborative project, the opera ''Four Sain ...

'' (opera, Virgil Thomson

Virgil Thomson (November 25, 1896 – September 30, 1989) was an American composer and critic. He was instrumental in the development of the "American Sound" in classical music. He has been described as a modernist, a neoromantic, a neoclassic ...

and Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein (February 3, 1874 – July 27, 1946) was an American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the Allegheny West neighborhood and raised in Oakland, California, Stein moved to Paris ...

), ''Measure for Measure

''Measure for Measure'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written in 1603 or 1604 and first performed in 1604, according to available records. It was published in the ''First Folio'' of 1623.

The play's plot features its ...

'' (William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

), '' Livin the Life'' (musical based on Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

's Mississippi River Tales), ''The Good Woman of Szechuan

''The Good Person of Szechwan'' (german: Der gute Mensch von Sezuan, first translated less literally as ''The Good Man of Setzuan'') is a play written by the German dramatist Bertolt Brecht, in collaboration with Margarete Steffin and Ruth Berlau. ...

'' (Bertolt Brecht

Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht (10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956), known professionally as Bertolt Brecht, was a German theatre practitioner, playwright, and poet. Coming of age during the Weimar Republic, he had his first successes as a pl ...

), ''Taming of the Shrew'' (William Shakespeare), ''Anna Christie

''Anna Christie'' is a play in four acts by Eugene O'Neill. It made its Broadway debut at the Vanderbilt Theatre on November 2, 1921. O'Neill received the 1922 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for this work. According to historian Paul Avrich, the orig ...

'' (Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright and Nobel laureate in literature. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of realism, earlier ...

).

Balancing these successes were two major impediments to Houghton's long term alliance to the Phoenix: their model resulted in a frenetic pace to their productions and they had persistent financial problems. Houghton recognized that they did not have a stable organizational structure or method to present theatre under a business plan that required appreciation by both establishment critiques and audiences. Most unsettling was the opinion that the Phoenix had not developed an appropriately unique viewpoint recognizable by respected critics. Houghton recognized other personal problems: he had become frustrated that the role of theatrical producer did not include his talents as designer and director.New York Times. 1961. Article by Myron Kandel. Pirates of Penzance to Bow Downtown as New Phoenix Plans to Rise Uptown. Despite injections of large amounts of money and enthusiasm the Phoenix' attempt to provide large scale off-Broadway theatre at low prices has failed.

Houghton considered as a solution to this dilemma an academic life that would allow him to couple academia with the role of theatre partner to T. Edward Hambleton, who would remain with the Phoenix until it closed. Initially, Houghton's movement into what would eventually become his full-time work as an academic was a mixture of teaching, writing, travel, and theater management. Houghton accepted a position as adjunct drama professor for the academic year 1959/1960 at Vassar College. In 1961 he returned to the Phoenix as co-managing director and helped achieve the goal to move into more appropriate space. The new home was a 300-seat house on East 74th Street

74th Street is an east–west street carrying pedestrian traffic and eastbound automotive/bicycle traffic in the New York City borough of Manhattan. It runs through the Upper East Side neighborhood (in ZIP code 10021, where it is known as East ...

, relieving them of the technical and financial issues related to the previous over-sized space. Their first production there was the spoof on Theatre of the Absurd

The Theatre of the Absurd (french: théâtre de l'absurde ) is a post–World War II designation for particular plays of absurdist fiction written by a number of primarily European playwrights in the late 1950s. It is also a term for the style of ...

written by Arthur Kopit

Arthur Lee Kopit (' Koenig; May 10, 1937 – April 2, 2021) was an American playwright. He was a two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist for '' Indians'' and ''Wings''. He was also nominated for three Tony Awards: Best Play for ''Indians'' (1970) an ...

, ''Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mamma's Hung You in the Closet and I'm Feelin' So Sad

''Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mamma's Hung You in the Closet and I'm Feelin' So Sad: A Pseudoclassical Tragifarce in a Bastard French Tradition'' was the first play written by Arthur Kopit.

Background

Kopit was on a postgraduate scholarship from Harvard ...

'', staged with wit and style by Jerome Robbins

Jerome Robbins (born Jerome Wilson Rabinowitz; October 11, 1918 – July 29, 1998) was an American dancer, choreographer, film director, theatre director and producer who worked in classical ballet, on stage, film, and television.

Among his nu ...

in his debut (and finale) as director of a straight play. (1,2,3,33,34,35)

Houghton then accepted a full-time position as professor, department chair and director of the Vassar Experimental Theatre Vassar may refer to:

* Vassar Brothers Medical Center

* Vassar College

* 1312 Vassar, an asteroid

People

* John Ellison Vassar (1813–1878), American lay preacher and missionary

* Matthew Vassar (1792–1868), American brewer and merchant, founder ...

, attempting a compromise of living in the Hudson valley while continuing to work in New York City. After three years, Houghton committed to a full-time academic life and Hambleton continued the Phoenix for another twenty years.

By the time of its closing in 1982, the Phoenix continued to nourish dramatists and young actors, including Marsha Norman

Marsha Norman (born September 21, 1947) is an American playwright, screenwriter, and novelist. She received the 1983 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for her play '' 'night, Mother''. She wrote the book and lyrics for such Broadway musicals as ''The Se ...

and Wendy Wasserman, Meryl Streep

Mary Louise Meryl Streep (born June 22, 1949) is an American actress. Often described as "the best actress of her generation", Streep is particularly known for her versatility and accent adaptability. She has received numerous accolades throu ...

, Glenn Close

Glenn Close (born March 19, 1947) is an American actress. Throughout her career spanning over four decades, Close has garnered numerous accolades, including two Screen Actors Guild Awards, three Golden Globe Awards, three Primetime Emmy Awards ...

, and Mary Beth Hurt

Mary Beth Hurt (''née'' Supringer; born September 25, 1946) is an American actress of stage and screen. She is a three-time Tony Award-nominated actress.

Notable films in which Hurt has appeared include ''Interiors'' (1978), ''The World Accordi ...

. "Off-Broadway" is now its own tradition of New York theater, and an impetus for many of the regional theatres that developed throughout the nation. Newer Phoenix theaters dedicated to similar principles have risen around the country: when a New York Phoenix opened less than a decade after the Houghton-Hambleton Phoenix closed, Bram Lewis contacted Houghton and Hambleton for permission to use the name. Houghton responded "Go ahead and good luck ... we remember when Sir Tyrone Guthrie

Sir William Tyrone Guthrie (2 July 1900 – 15 May 1971) was an English theatrical director instrumental in the founding of the Stratford Festival of Canada, the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and the Tyrone Guthrie Centre at his ...

went out and spoke up on our behalf. That's the proper way to proceed in theater."

Academia: transmitting theatre to a new generation

Houghton's academic career followed a non-traditional pattern for a number of years. Beginning in the 1950s, he was offered coveted positions in a number of prestigious colleges and university, for years he moved in and out of these positions, combining them with an active life in the theater and as an analyst, interpreter, and author of global theater. In 1960, he returned to Russia on a second Guggenheim Fellowship that led to Return Engagement, the postscript to Moscow Rehearsals. In 1965, he went to Germany at the invitation of the West German government to tour its theatrical centers. Shortly after returning he received an invitation to visit Korea, funded by theRockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, after the Carneg ...

, to guide a theatre project in Seoul

Seoul (; ; ), officially known as the Seoul Special City, is the capital and largest metropolis of South Korea.Before 1972, Seoul was the ''de jure'' capital of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) as stated iArticle 103 ...

. From Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

he was welcomed to visits in Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

, Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand t ...

, and Kathmandu

, pushpin_map = Nepal Bagmati Province#Nepal#Asia

, coordinates =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name =

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 = Bagmati Prov ...

, augmenting his understanding of theatre.

Houghton taught at Columbia, Princeton, Smith College

Smith College is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts Women's colleges in the United States, women's college in Northampton, Massachusetts. It was chartered in 1871 by Sophia Smith (Smith College ...

, Union Theological Seminary, Yale, Barnard Vassar College, New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then-Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, the ...

, Harvard, University of Louisville

The University of Louisville (UofL) is a public research university in Louisville, Kentucky. It is part of the Kentucky state university system. When founded in 1798, it was the first city-owned public university in the United States and one of ...

, Lynchburg College

The University of Lynchburg, formerly Lynchburg College, is a private university associated with the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) and located in Lynchburg, Virginia. It has approximately 2,800 undergraduate and graduate students. ...

, Shanghai Drama Academy, and SUNY Purchase. At an earlier stage he taught theatre history from 1936 to 1939 at the Finch School

Finch College was an undergraduate women's college in Manhattan, New York City. The Finch School opened as a private secondary school for girls in 1900 and became a liberal arts college in 1952. It closed in 1976.

Founding

Finch was founded in 1 ...

in New York City, a small prestigious high school for girls. After his World War II service ended, he rejoined Princeton to participate full-time in the Creative Arts Program while completing his book ''Advance From Broadway''.

At Vassar College, from 1962 to 1967, he was full professor and chair of the drama department.Norwalk Hour. May 8, 1967. College Students to Stage Benefit for Vassar Club. From there he went to join the State University of New York's newly envisioned college at Purchase, New York.http://www.Purchase.edu. Purchase College notes its traditions for excellence began with its founding Dean, Norris Houghton.

Houghton's books, personal papers, playscripts, and other writings are held in collections at the Century Club in New York City and in university libraries and rare book collections, including Vassar, Princeton, Columbia, and Ohio State.

Advocacy for arts education as national policy

In 1973, concurrently with his deanship at Purchase, Houghton became president of the American Council for the Arts in Education. Houghton proposed a public panel report from distinguished objective citizens, rather than established arts educators, about arts education as a national priority.David Rockefeller Jr.

The Rockefeller family () is an American industrial, political, and banking family that owns one of the world's largest fortunes. The fortune was made in the American petroleum industry during the late 19th and early 20th centuries by broth ...

, chair of what became the Arts, Education and Americans Panel, was recruited by vice-chair Houghton. That made fundraising and attraction of a high level panel easier. The short term effects of this effort are seen in the 1977 panel report, ''Coming To Our Senses: The Significance of the Arts for American Education'', and numerous national programs supporting the arts in educational settings.http://www.rockarch.org/collections/rockorgs/miscorgs.php. Finding Aids Rockefeller Foundation Files. Arts, Education, and Americans Panel. Norris Houghton Files, Series 4. Papers of Norris Houghton as Chair of panel recommending arts education in America.

Finale

After retirement, Houghton lived an active life with such stints as Visiting Distinguished Professor at the University of Louisville reflecting the long term devotion of Barry Bingham, head of the ''Louisville Courier-Journal

The ''Courier Journal'',

also known as the

''Louisville Courier Journal''

(and informally ''The C-J'' or ''The Courier''), and called ''The Courier-Journal'' between November 8, 1868, and October 29, 2017,

is the highest circulation newspape ...

'' newspaper dynasty, and writing his memoir, ''Entrances and Exits: A Life In and Out of the Theatre''. John Russell described it in the New York Times: "By his own account Norris Houghton is the most contented of men, and rightly so. When he was 11 years old, all of 70 years ago, he decided his role in life would be to put on good plays and get people to come and see them. He did it at home, he did it in school and he did it at Princeton University, where as an undergraduate he fell in with more than one future luminary of the American theater. He did it everywhere and all the time. It did not... win him either fame or fortune, but some great adventures resulted. And if today there is first-rate theater in New York that is not on Broadway, and if there are towns all over the United States that pride themselves on their local theaters, something may be owed to the example of Norris Houghton."

He died in 2001 and was celebrated by a full-choir funeral ritual at First Presbyterian Church in the City of New York, where as long-time member and Elder he had coaxed the historic Manhattan congregation into sponsoring a Phoenix series of plays by Nobel prizewinners including dramas with religious themes.

Norris Houghton wrote articles for: ''American Scholar

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

''; '' Arts in Society''; ''Atlantic Monthly

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher. It features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 in Boston, ...

''; '' Educational Theatre Journal'', ''Harper's Bazaar

''Harper's Bazaar'' is an American monthly women's fashion magazine. It was first published in New York City on November 2, 1867, as the weekly ''Harper's Bazar''. ''Harper's Bazaar'' is published by Hearst and considers itself to be the st ...

'', ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

'', '' New Theatre Magazine'', ''The Russian Review

''The Russian Review'' is an independent peer-reviewed multi-disciplinary academic journal devoted to the history, literature, culture, fine arts, cinema, society, and politics of the Russian Federation, former Soviet Union and former Russian Empir ...

'', ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

''; ''The Drama Review

''TDR: The Drama Review'' is an academic journal focusing on performances in their social, economic, aesthetic, and political contexts. The journal covers dance, theatre, music, performance art, visual art, popular entertainment, media, sports, r ...

''; '' The Saturday Review''; ''Stage

Stage or stages may refer to:

Acting

* Stage (theatre), a space for the performance of theatrical productions

* Theatre, a branch of the performing arts, often referred to as "the stage"

* ''The Stage'', a weekly British theatre newspaper

* Sta ...

''; ''Theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perform ...

''; ''Theatre Arts''.

Awards/Honorary Memberships

*Guggenheim Fellowships, 1934–1935; 1960–1961 *Rockefeller Foundation Grant-in-Aid, 1940–1941 *Excellence in Theater Award, 1958 New England Theater Conference *Advisory Council, Institute for Advanced Studies in Theatre Arts, 1959 *Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts, Denison University, 1959 *Obie Award

The Obie Awards or Off-Broadway Theater Awards are annual awards originally given by ''The Village Voice'' newspaper to theatre artists and groups in New York City. In September 2014, the awards were jointly presented and administered with the A ...